Monad

Monad extends the Applicative type class with a

new function flatten. Flatten takes a value in a nested context (eg.

F[F[A]] where F is the context) and "joins" the contexts together so

that we have a single context (ie. F[A]).

The name flatten should remind you of the functions of the same name on many

classes in the standard library.

scala> Option(Option(1)).flatten

res0: Option[Int] = Some(1)

scala> Option(None).flatten

res1: Option[Nothing] = None

scala> List(List(1),List(2,3)).flatten

res2: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

Monad instances

If Applicative is already present and flatten is well-behaved,

extending the Applicative to a Monad is trivial. To provide evidence

that a type belongs in the Monad typeclass, cats' implementation

requires us to provide an implementation of pure (which can be reused

from Applicative) and flatMap.

We can use flatten to define flatMap: flatMap is just map

followed by flatten. Conversely, flatten is just flatMap using

the identity function x => x (i.e. flatMap(_)(x => x)).

scala> import cats._

import cats._

scala> implicit def optionMonad(implicit app: Applicative[Option]) =

| new Monad[Option] {

| // Define flatMap using Option's flatten method

| override def flatMap[A, B](fa: Option[A])(f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] =

| app.map(fa)(f).flatten

| // Reuse this definition from Applicative.

| override def pure[A](a: A): Option[A] = app.pure(a)

| }

optionMonad: (implicit app: cats.Applicative[Option])cats.Monad[Option]

flatMap

flatMap is often considered to be the core function of Monad, and cats

follows this tradition by providing implementations of flatten and map

derived from flatMap and pure.

scala> implicit val listMonad = new Monad[List] {

| def flatMap[A, B](fa: List[A])(f: A => List[B]): List[B] = fa.flatMap(f)

| def pure[A](a: A): List[A] = List(a)

| }

listMonad: cats.Monad[List] = $anon$1@58491bc5

Part of the reason for this is that name flatMap has special significance in

scala, as for-comprehensions rely on this method to chain together operations

in a monadic context.

scala> import scala.reflect.runtime.universe

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe

scala> universe.reify(

| for {

| x <- Some(1)

| y <- Some(2)

| } yield x + y

| ).tree

res3: reflect.runtime.universe.Tree = Some.apply(1).flatMap(((x) => Some.apply(2).map(((y) => x.$plus(y)))))

ifM

Monad provides the ability to choose later operations in a sequence based on

the results of earlier ones. This is embodied in ifM, which lifts an if

statement into the monadic context.

scala> Monad[List].ifM(List(true, false, true))(List(1, 2), List(3, 4))

res4: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2)

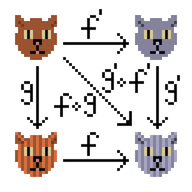

Composition

Unlike Functors and Applicatives,

not all Monads compose. This means that even if M[_] and N[_] are

both Monads, M[N[_]] is not guaranteed to be a Monad.

However, many common cases do. One way of expressing this is to provide

instructions on how to compose any outer monad (F in the following

example) with a specific inner monad (Option in the following

example).

scala> case class OptionT[F[_], A](value: F[Option[A]])

defined class OptionT

scala> implicit def optionTMonad[F[_]](implicit F : Monad[F]) = {

| new Monad[OptionT[F, ?]] {

| def pure[A](a: A): OptionT[F, A] = OptionT(F.pure(Some(a)))

| def flatMap[A, B](fa: OptionT[F, A])(f: A => OptionT[F, B]): OptionT[F, B] =

| OptionT {

| F.flatMap(fa.value) {

| case None => F.pure(None)

| case Some(a) => f(a).value

| }

| }

| }

| }

optionTMonad: [F[_]](implicit F: cats.Monad[F])cats.Monad[[β]OptionT[F,β]]

This sort of construction is called a monad transformer.